I started my career as an occupational therapist. My job was to help people relearn how to do things in their everyday life after experiencing an illness or disability. To do this I had to do two things: firstly, I had to analyse the task to establish exactly what the person needed in order to be able to carry out the task and secondly I had to find out what they could and could not do. Only then could I develop a plan to help them master the task. I have applied this same approach – task analysis and assessment of skills and knowledge – to the process of teaching and learning literacy skills.

Mastering a skill of any sort usually involves learning strategies and techniques with lots of practice to hone the skill so that it can be used in different situations. Think about how we teach young children to play a sport. Children who want to play football for example, spend a lot of time learning the skills of ball handling, working with others and understanding the rules of the game. With those skills in place, they are then ready to start playing a game of football.

Whether children start playing football as pre-schoolers or come to the game later, they still have to master these skills and learn the rules of the game. Practice sessions continue to teach and refine these skills and budding footballers spend a lot of time honing their skills so that they can use them automatically and efficiently in a game.

This approach to teaching a sport works well when teaching literacy. Writing and reading are complex processes. Just like a game of football, they require the ‘player’ to master a range of skills and knowledge and to understand how to use them. Just like in football, some children pick up the skills effortlessly and master them with only a small amount of practice. Others take longer, and some decide that football is not for them because the skills required seem too hard to master. Being able to read and write is not like football – playing football is optional, learning to read and write is not. The way we teach children to read and write has to be successful. We need to explicitly teach the skills and knowledge they need to learn if they are to become successful readers and writers.

So what does explicit instruction mean for literacy?

It means understanding what is involved in learning to read and write. It means finding out what skills and knowledge students already have and where they have gaps. It means using assessment to drive instruction – to teach the skills and knowledge students have not mastered but need to learn. Sometimes this means whole class instruction and sometimes it means giving students the extra instruction and practice they need in small groups or individually.

Explicit instruction to close the gaps

I wrote ‘Catch Up Your Code’ and ‘Sort Out Your Syllables’ to address gaps in literacy knowledge for students in upper primary and secondary classrooms. From Year 5 and beyond, students are required to read more and more complex texts in subject areas that are often new to them. The language is more formal, and many words are multisyllabic, abstract and technical. Students who have not mastered the ability to decode automatically and efficiently will struggle. It is estimated that the average fifth year student encounters about ten thousand new words – described as an “orthographic avalanche” that overwhelms most of those without adequate decoding skills.

Teach decoding explicitly

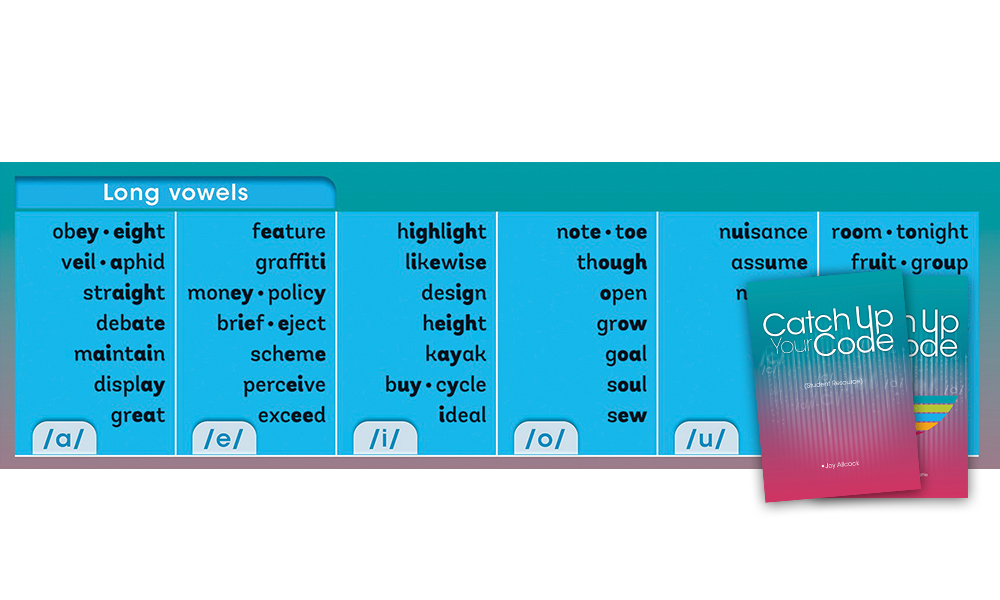

If decoding is not automatic, the skills and knowledge needed must be taught explicitly. First and foremost, students need an in-depth knowledge of how the alphabetic code of English works. ‘Catch Up Your Code’ teaches this. To decode efficiently, students must recognise graphemes and be able to pronounce them in different ways. Once they have a conscious understanding of the diverse nature of grapheme-phoneme relationships, they can use this knowledge as a foundation for learning to decode unfamiliar multisyllabic words.

That’s where ‘Sort Out Your Syllables’ comes in. Students use their knowledge of the code for the vowel sounds of English, to find and pronounce syllables in unfamiliar words. These two areas of knowledge and skill – alphabetic code knowledge and strategies for decoding multisyllabic words – will dramatically improve decoding skills in the upper years. If decoding isn’t efficient by Year 5, it will not become so, without explicit instruction that targets gaps in knowledge and skills.

Sorting vowel spelling patterns – the key to finding syllables in words

These Year 7 and 8 students are working collaboratively to learn about the nine types of vowel spelling patterns they will find in syllables.

Teach the skills for writing explicitly

From Year 5 onwards, students are required to write longer, more complex scripts in different writing genres. The expectation is that they should have mastered the foundation skills for writing: to write speedily and legibly, to spell most high-frequency words correctly, to use spelling strategies to spell most words close to correctly, to write in paragraphs, to use punctuation correctly, to proofread their writing for spelling and punctuation errors, to revise and edit their work to improve the content. Unfortunately, many students who find handwriting and correct spelling a challenge will struggle to master the other higher-order skills of writing, regardless of their potential to write as well as they can speak.

The way to improve writing skills is to explicitly target the areas that need improvement, starting with the foundation skills. If handwriting is a major challenge by Year 5, students may be best to use a digital device to avoid illegible handwriting hindering their writing progress.

If they struggle to spell words correctly, a range of strategies are needed. Firstly, students need to be able to write every sound of English in at least one way and they also need knowledge of the diversity of the code. ‘Catch Up Your Code’ teaches this. They need to know how to write multisyllabic words they can say but not spell. ‘Sort Out Your Syllables’ teaches this.

They then need to learn about the spelling system of English – the rules and conventions that affect why words are written the way they are. Once they are fluent in getting words on the page in a form that can easily be read – even if they are not all spelt correctly – they can then be taught strategies for punctuation and paragraphing, authorship, proofreading and editing. All the skills for writing need to be taught explicitly, starting with those that build the foundation for authorship.

Summary

Explicit instruction for literacy is simply targeting the knowledge and skills that research has shown to be essential for students to learn to read and write, and ensuring they are taught in a logical, sequential and direct way. It doesn’t matter whether students have just started school or have been at school for a while – everyone benefits from explicit instruction.

Use assessments to find out what students know and can do. Teach what they need to learn.

Check they have learned it. Leave nothing to chance.

The way we teach has to ensure all students become successful readers and writers. Teaching skills and knowledge explicitly is the best way to ensure this happens.

Featured Products:

About the Author

Joy Allcock (M.Ed). Independent Literacy consultant, facilitator of teacher professional

development throughout New Zealand and internationally. Presenter at NZ and international literacy conferences (IRA, ASCD/ACEL). Author of a range of literacy resources for teachers and students (www.joyallcock.co.nz). Leader of Shine Literacy Research Project (designed and evaluated by Massey University – www.literacysuccess.org.nz)