We are faced with unprecedented challenges in education at the moment. Teachers are juggling face-to-face teaching and distance learning and wondering what they should do to maximise learning opportunities for their students. John Hattie has some wise advice.

“We should focus on the things that can have the greatest impact and stop being distracted by the things that don’t matter.”

Ref: https://visible-learning.org/

So what can we do to have the greatest impact on our students’ literacy outcomes?

We live in an age of information, with language the key to participation. Priscilla Vail 1 says, “For our society to function, for people to make productive use of the tidal waves of information available through electronics, we need the skills of sorting, prioritising, and organising which language offers. For individuals to participate and grow, we need well-honed communication skills.”

Vail was referring to the need to develop rich oral language skills and these are of course the foundation for all communication, whether it be spoken or written.

From birth, children begin the life-long journey of learning how to use language to communicate – a process that is innate in humans. They are exposed to written forms of language from an early age, but most do not begin the task of learning to use written language until they go to school. Learning how print works is not innate – it has to be taught.

Written languages fall broadly into two types – logographic languages, which use visual images to represent words (Chinese, Korean, Japanese, for example) and phonologic languages, which use symbols to represent the sounds that make up spoken words (English, Spanish, German, for example). Some phonologic languages have one-to-one relationships between sounds and symbols (Spanish, Italian, Finnish, for example) and others have diverse relationships (English, French, for example). Young children learning to read and write the language they speak must therefore learn to understand the symbols that represent either the words they speak, or the sounds that make up the words they speak.

Written English is a complex sound-symbol language. There are many different ways that sounds (phonemes) can be written (the /k/ sound for example – cat, kite, soccer, pack, queue, quay, school), and many different ways that the symbol (graphemes – letters and letter patterns) can be pronounced (chips, chef, school; apple, apron, was, water, fast, for example).

Understanding that words are made up of sounds and that sounds can be written using letters and letter patterns is an understanding of the alphabetic principle. Learning how phonemes and graphemes map to each other is learning about the alphabetic code. In some languages this is a relatively straightforward task. In English it is much more difficult because of the diversity that exists between how letters and letter patterns are pronounced and how sounds are written.

For anyone learning to read and write English, understanding how the alphabetic code works is essential. It is not something that is easy to ‘pick up’ through exposure to print. The way the code works must be explicitly taught. Phonics programmes are typically used to teach the alphabetic code in the early years. There are a large number of phonics programmes available and used in our schools and they vary in their accuracy and efficacy. It is often difficult for teachers to know how to evaluate the efficacy of such programmes and what to do if they do not produce the desired results.

I have been helping students learn how the alphabetic code of English works for more than 20 years. This is what I have learned.

-

- Teach from sound to print – use what children already know (the sounds in words) to teach what they don’t know (the English code that forms written words).

- Teach phonemic awareness skills – so that children can take words apart and put them back together again as they use their knowledge of the alphabetic code to read and write words that they do not yet have in their print memory.

- Teach the alphabetic code beyond the early years.

There are close to 300 graphemes that represent the 43 phonemes of English. Many of these are not in words that young children meet in the first two years at school. We cannot teach everything that students need to know about the alphabetic code in the first two to three years.

A lack of knowledge of how the alphabetic code works has a negative impact on reading and writing.

When you are reading, if you come to a word that is unfamiliar, you need to use your knowledge of the code and your phonemic awareness skills to link to the sounds that make up the word to sound it out. If you want to write a word you cannot spell, you need to sound it out and write the code for the sounds that make up the word. Fluency with reading and writing is negatively impacted by a lack of knowledge of the alphabetic code and poor phonemic awareness skills.

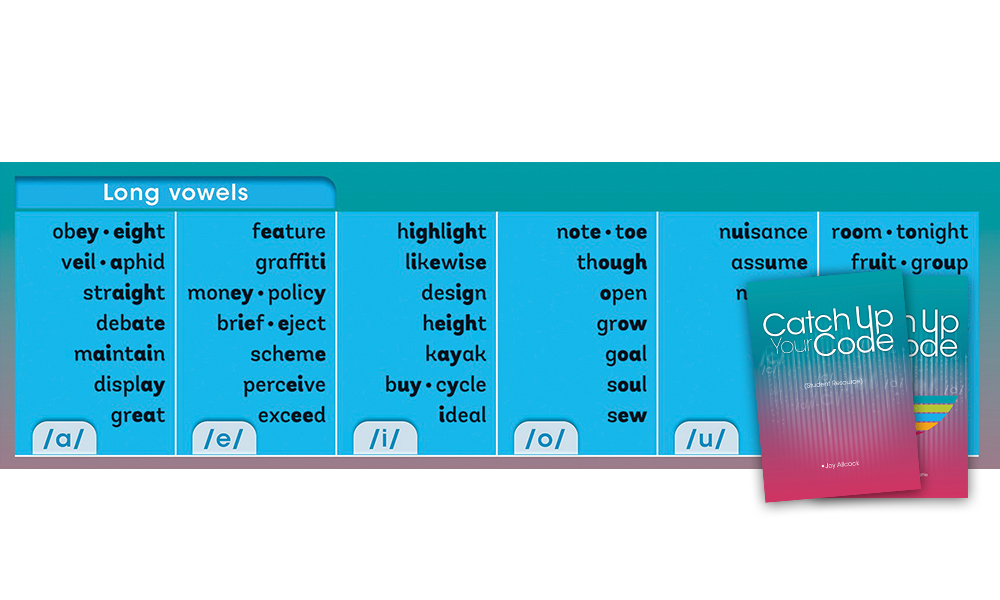

Catch Up Your Code is a book that has been written to quickly address the gaps in code knowledge for students from Year 4 to adults. By Year 4, students have been exposed to a lot of print and they will have a large bank of words they know both orally and in their written form. However, despite having lots of words in their print memory, many students are still unable to use the alphabetic code because they do not have conscious knowledge of it.

Catch Up Your Code uses a simple but effective strategy that helps students (and teachers!) think differently about how words work. Students are asked to think of words that contain a target sound and to write these words and find the code for the target sound. They quickly learn about the diversity of the code and begin to discover some of the conventions about how and when it is used. They learn to sort, prioritise and organise what they already knew, as well as what they have just learned about how the alphabetic code is used to represent spoken words.

Alphabetic code knowledge is the foundation for learning to read and write English. It is fundamental to becoming a successful reader and writer. Students cannot have gaps in this knowledge. They must have a deep knowledge of how it works and strategies that help them use this knowledge as they read and write unfamiliar words.

Using Catch Up Your Code for 10 minutes a day for a term will consolidate the code knowledge your students already have and fill in the gaps of what they don’t know, so that they have a deep knowledge base to refer to as they tackle reading and writing texts that are more and more complex.

Knowledge of the alphabetic code does matter. If you can find 10 minutes a day to use a simple but effective strategy for increasing students’ knowledge of the foundation of written English, it will have a significant impact on their reading and writing outcomes.

1 Vail., P., L. (1996). Words Fail Me. How language works and what happens if it doesn’t. Modern Learning Press. Rosemont. NJ.

Featured Product:

About the Author

Joy Allcock (M.Ed). Independent Literacy consultant, facilitator of teacher professional

development throughout New Zealand and internationally. Presenter at NZ and international literacy conferences (IRA, ASCD/ACEL). Author of a range of literacy resources for teachers and students (www.joyallcock.co.nz). Leader of Shine Literacy Research Project (designed and evaluated by Massey University – www.literacysuccess.org.nz)